Luke 12

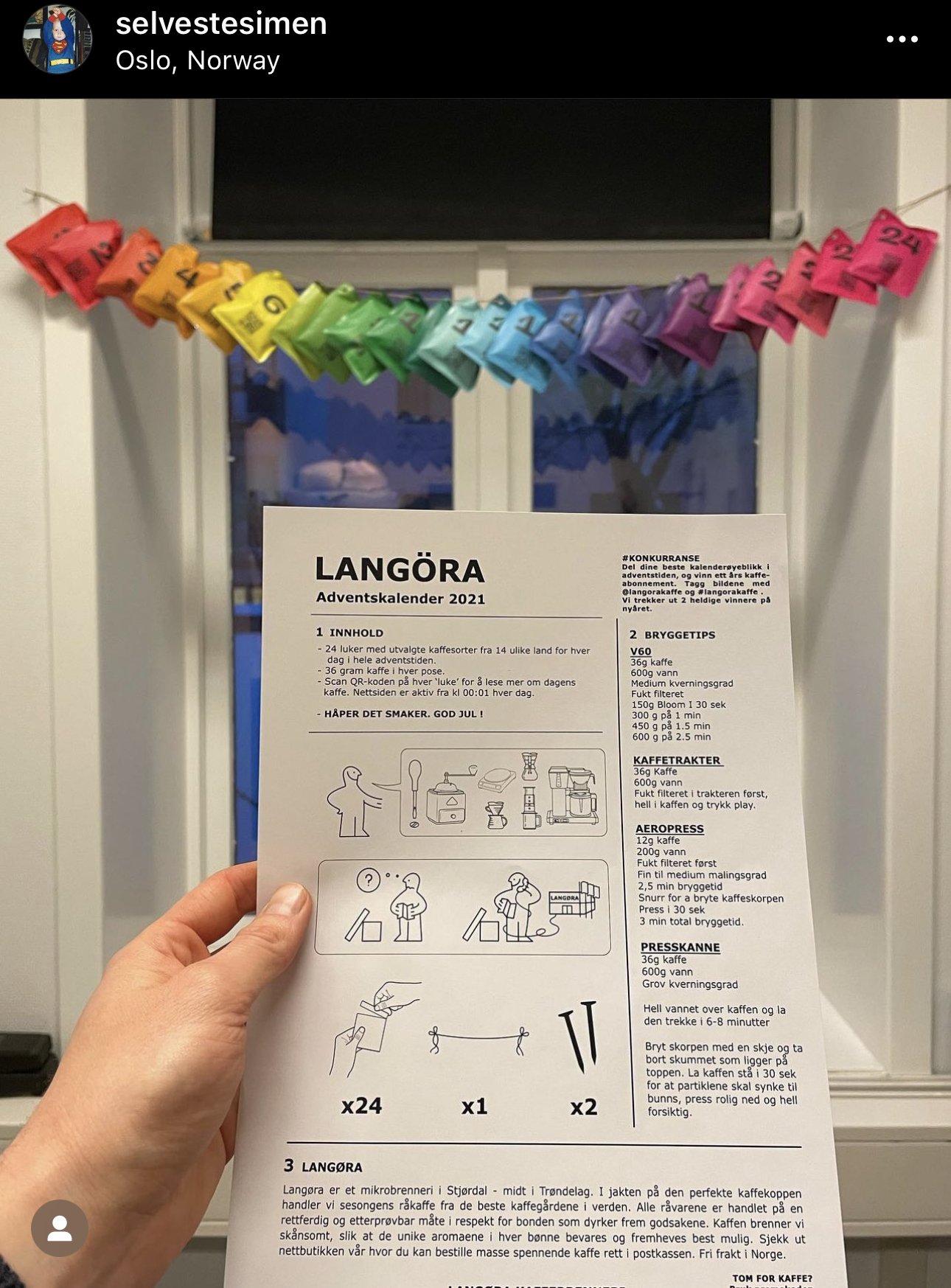

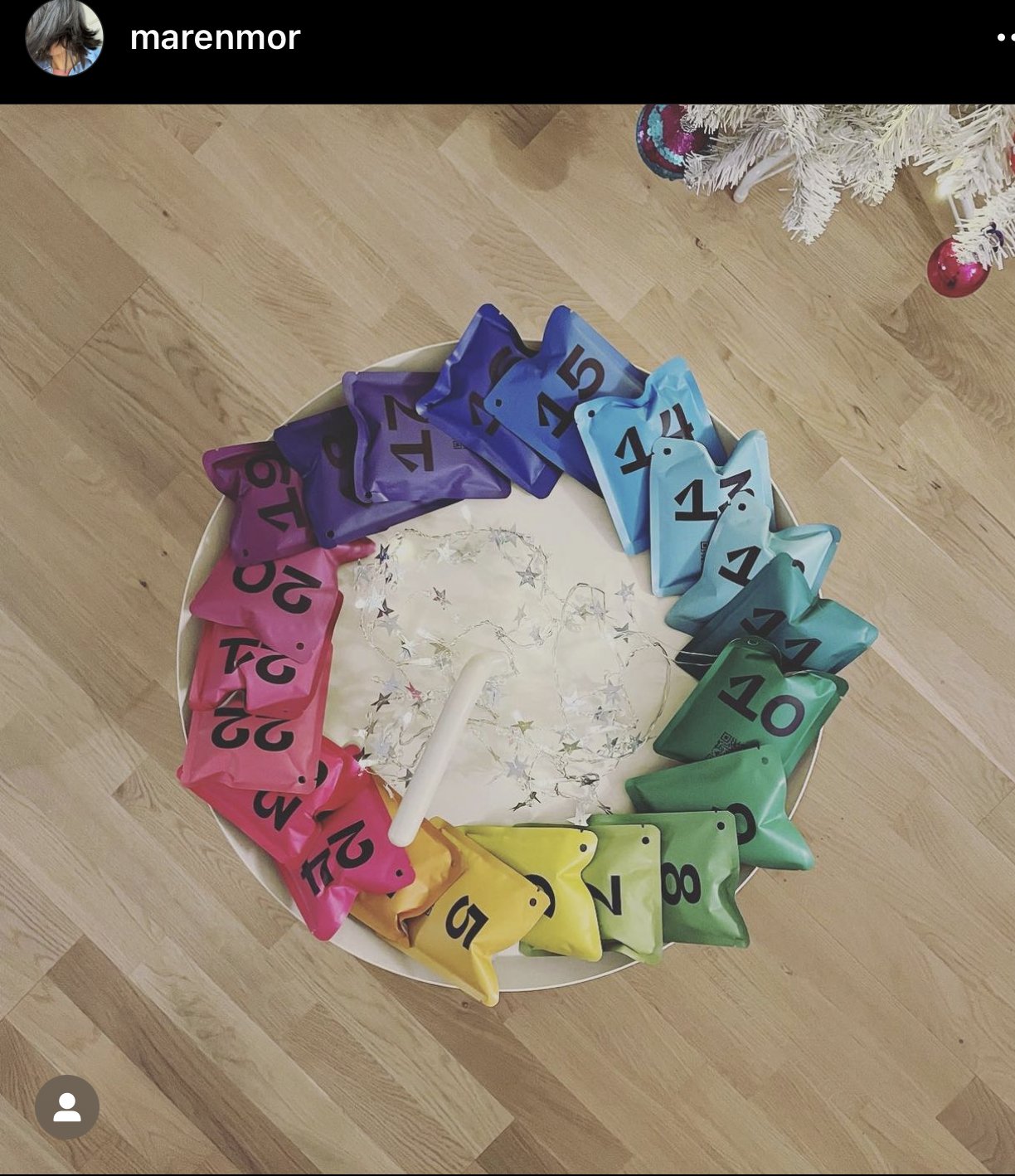

KonkurRanse:

Del dine bilder og videoer av Langøras adventskalender på TikTok, Instagram og Facebook under #langørakaffe og @langorakaffe .

Vi trekker tre vinnere som får 6 måneders kaffeabonnement på nyåret.

(ved å delta i konkurransen godtar du at vi kan bruke bildene i markedsføring)

Lộc Rừng

COUNTRY: Vietnam

VARIETAL: Liberica / Excelsa

PROCESSING: anaerobic / natural

ALTITUDE: 600 m.a.s.l.

PRODUCER: 96B

SUBREGION/TOWN: Quang Tri

REGION: Saigon

HARVEST MONTHS: Apr. 2025 - May 2025

FLAVOUR NOTES: Very distinctive with an umami-like quality, black cherry candy, vanilla, ripe strawberries, roses, a little bit like diesel but in a pleasant way?

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

Coffea Liberica, discovered in 1872 in Sierra Leone and described before Canephora (Robusta), represents less than 1% of the global coffee market but stands out for its exceptional complexity. Native to Liberia and now grown mainly in Malaysia, the Philippines, and parts of Africa and Latin America, Liberica produces large trees reaching up to 15 meters with broad leaves and oversized cherries. It contains the highest sugar content of all coffee species, resulting in naturally sweet, full-bodied cups with aromas ranging from fruity and floral (jackfruit, mango, banana) to lactic and creamy (mascarpone, cream). The beans are yellowish to light green and, when lightly roasted, reveal notes of caramel, vanilla, and apple. Even small additions of Liberica—around 5%—can significantly enhance the sweetness and mouthfeel of blends.

Cultivation and Harvest

This anaerobically processed natural is, according to recent findings, a farm blend of Coffea liberica and Coffea dewevrei (Excelsa). The cherries undergo dry fermentation for 120 hours in airtight PE bags and are then dried for 30 days on shaded raised beds.

Liberica trees require more space (about 5×5 m) and produce relatively low yields, needing around 10 kg of cherries to make 1 kg of green coffee. Despite this, they offer strong agricultural advantages: high resistance to nematodes and complete immunity to coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix). These traits make Liberica an ideal rootstock for weaker varieties, contributing to notable hybrids such as India’s celebrated S. 795, valued for its sweetness and body. In cultivation, the species has a unique ecological role due to its sugar-rich cherries, which attract the coffee borer beetle (broca). Farmers have long used Liberica trees as natural pest traps—earning them nicknames like “Broca Hotel” or “sacrifice tree.” Today, limited harvesting occurs mainly on small estates, such as Badra and Palthope in India, where renewed interest aims to revive and study the species.

COFFEE IN VIETNAM

PLACE IN WORLD PRODUCTION: #2

AVERAGE ANNUAL PRODUCTION:

30,850,000 (in 60kg bags)

COMMON ARABICA VARIETIES:

Catimor, with some Typica & Bourbon

KEY REGIONS:

Central Highlands (Lam Dong province) | North Vietnam (Son La, Dien Bien provinces)

HARVEST MONTHS:

Central Highlands: November - January | North Vietnam: October - January

Vietnam has a long, complex cultural history. There is evidence that early humans settled in the region at least 500,000 years ago, and the first Vietnamese states occurred nearly 5,000 years ago.

In the modern era, Vietnam was occupied by French troops during their first attack on Danang in 1858. Following this, as in so many other colonized countries, coffee came to Vietnam on the ships of French missionaries. The missionaries trialed different regions across Vietnam before determining that the Central Highlands were the best place to cultivate coffee. Interestingly enough, the first coffee planted in Vietnam was Arabica, not the Robusta that is so widely grown there today.

Robusta did not arrive in Vietnam until nearly 30 years later when, in 1908, the French brought Robusta, along with another variety, Excelsa, to the Central Highlands. Even after the arrival of Robusta, Vietnam did not immediately become the Robusta-producing giant that we know it to be today. The area under coffee cultivation continued to grow slowly.

In the 20th century, Vietnam suffered two decades of horrific violence and destruction (1955-1975) that left the country suffering for many years after the war had ceased. The Đổi Mới (Vietnamese for “Renovation”) reforms were launched by the government in 1986 in an effort to boost the country’s economy and world-wide standing. , These reforms broke from Vietnam’s previously insular politics. Importantly, the let Vietnam enter the global market and allowed private enterprise. They also allowed privatization of land, which presented an opportunity for increased agricultural productivity. The government also focused resources on investing in the coffee industry with the intention of making it a key cash crop. They initiated state-funded farms and encouraged households to grow coffee on their own lands. Unsurprisingly, production has grown astronomically since the introduction of the reforms.

Another area of focus has been continued investment in research. A number of research institutions across Vietnam have focused on creating new hybrids and improving grafting techniques. As a result, farmers have access to a wide range of Robusta varieties to help them maintain healthy and disease-resistant rootstock.Today, with a total production of about 30 million bags, around 95% of coffee grown in Vietnam is Robusta. Vietnam has the highest yields globally with an output of 2.8 tons of coffee per hectares. This is a full ton higher than the second-highest yield of 1.4 tons per hectare in Brazil.

While Vietnam is 13th in global Arabica production volumes, when Robusta production is included, Vietnam ranks second in the world for total coffee volume. Only Brazil has a higher production volume.

Privately run farms compose 95% of coffee farms in Vietnam today. Estimates suggest that about 85% of total production area is cultivated by households. Of the area farmed by households, 63%—or approximately 650,000 families—are smallholders with less than one hectare. The remaining 5% are state-run but that number is gradually shrinking as the land is redistributed to small farmers.

Natural processing is the most common method, where cherry is typically sundried on plastic tarps. In the past, little attention was given to quality differentiation during post-harvest activities. This, however, is changing rapidly.

From the beginning of the Đổi Mới reforms to around the end of the International Coffee Agreement in 1989, the government purchased all coffee grown in Vietnam at set prices. Since all coffee received the same price, there was little incentive to improve cup quality or cultivate the more-difficult-to-grow Arabica.

Today, the growth of the specialty coffee industry, combined with low prices for commercial coffee, has sparked farmers’ interest in growing higher quality Robusta coffee and venturing into Arabica cultivation.

The main variety planted in Vietnam is Catimor, a hybrid of Caturra and Timor (itself an Arabica-Robusta hybrid). While Catimor boasts high yields and high disease-resistance, it’s not typically prized for its cup quality. So, many producers are turning to other varieties to produce more dynamic and higher-paying coffees.

Producers are also focusing on improving their selection and processing techniques. This focus on improvement begins at harvest time. Farmers and their workers have begun to employ more selective harvesting techniques, and better post-harvest quality controls are increasingly being implemented.

Other producers are venturing into experimental processing to increase harvest quality and, ultimately, sale price. Some producers are focusing on yeast or enzyme fermentations, others are using anaerobic fermentation. At this point, most of this experimentation is used on microlots. In the future, more farmers may turn to processing most or all of their harvest using advanced or experimental processes to help increase sale prices.