Luke 24

Wilton Benitez Geisha

COUNTRY: Colombia

FARM/COOP/STATION: La Macarena

VARIETAL: Geisha

PROCESSING: Anaerobic fermentation + thermoshock.

ALTITUDE: 1900 meters

OWNER: Wilton Benitez

REGION: Huila

FARM SIZE: 14 hectares

FLAVOUR NOTES: Jasmine, citrus peel, light honey, mandarin, black tea, malt

ABOUT THE FARMER

The family farm of Wilton Benítez has established itself as a benchmark in the production of high quality coffees, standing out for its dedication to excellence and innovation. Growing exceptional varieties such as Java, Pink Bourbon, Geisha, SL-28 and Caturra, the farm offers beans with sensory profiles that surprise coffee lovers. The combination of traditional techniques with modern systems, such as terraces and drip irrigation, allows for optimal crop management. In addition, a nutritional approach based on laboratory analysis ensures that each stage of the process is rigorously controlled, culminating in the production of coffees that not only win international awards, but also provide a unique experience in every cup. These efforts reflect the farm's commitment to maintaining its reputation and continuing to surprise the coffee world.

Anaerobic fermentation and thermal shock

When the fruits are ripe, they are harvested by hand at their optimal point of ripeness. The coffee fruit is then sorted by quality, both by size and density.

It is then subjected to two sterilisation processes:

* First, the fruit is washed with ozonated water.

* The second, the same fruit is exposed to ultraviolet rays.

The coffee cherries then undergo two stages of fermentation:

* The first is 50 to 60 hours of anaerobic fermentation at a temperature of no less than 18 °C, during which time yeast selected for the varietal or micro-batch of coffee is added. All this takes place in stainless steel fermentation tanks (bioreactors), which allow the pressure generated by fermentation to be controlled in order to bring the Brix to 6 and the pH to 3.8.

During this first fermentation phase, the mucilage is recovered and reincorporated into the fermentation environment in the next phase.

The cherries are pulped or skinned before moving on to the second phase:

*Second phase: They are returned to the bioreactors, where anaerobic fermentation in mucilage begins for 50 to 60 hours at a temperature above 21 °C.

They are then washed using a thermal shock method: first with water between 38 and 40 °C and then with cold water at approximately 12 °C. The temperature difference helps to fix the aromas produced by fermentation and to sterilise according to the temperature.

Finally, the cherries are dried in an ecological machine that allows for temperature control and recovery of the water released by the dehydration of the bean. Drying usually takes 36 hours at a variable temperature (40 °C for the first 12 hours and 35 °C for the following 24 hours).

Once the seeds from the micro-batches have a moisture content of between 11% and 10%, they are taken to the storage warehouse where they are sorted electronically and manually to meet the required physical quality standards.

Once they have the desired physical characteristics, samples are taken to the laboratory for quality verification and tasting.

The use of bioreactors, innovative drying systems, specific microorganisms developed on the farm , and constant monitoring and control of factors such as temperature, pH, Brix degrees and electrical conductivity allow for the development of more balanced coffees, with abundant tropical fruits (passion fruit, lychee, pineapple, tamarind, coconut...), providing exceptional micro-batches now available to roasters.

COFFEE IN COLOMBIA

Although coffee production in Colombia did not become a large commercial industry until the 19th century, it is likely that coffee was introduced to Colombia about a century earlier by Jesuit priests.

Once commercial production started, it spread quickly. The first commercial coffee plantations were established in the northeast, near the border with Venezuela. Today, coffee is widespread and grown commercially in 20 of Colombia’s 32 Departments.

Historically, Colombia’s most renowned coffee-growing region has been the Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis), also known as the ‘Coffee Triangle’. This region includes the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. With a combined total area of 13,873 km² (5356 mi²), the region covers about 1.2% of the Colombian territory and composes 15% of the total land planted under coffee in the country. The region has also been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the Eje Cafetero is still a coffee-producing powerhouse, coffee production in Colombia now extends far beyond this zone. In recent years, the departments of Huila, Tolima, Cauca and Nariño have become sought after and well-known coffee-growing regions. Today, they are the largest producers of coffee in Colombia by volume.

Today, there are an estimated 540,000 coffee producers in the country; around 95% of these are smallholder farmers with landholdings that are under 5 hectares. These farmers collectively contribute around 16% of the country’s annual agricultural GDP.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 23

Jairo Arcila Passionfruit

COUNTRY: Colombia

FARM/COOP/STATION: Santa Mónica

VARIETAL: Castillo

PROCESSING: Washed Wine Yeast / Passionfrui

OWNER: Jairo Arcila

REGION: Quindio

FLAVOUR NOTES: Passionfruit, lemon verbena, orange blossom, apricot

ABOUT THIS FARMER

Jairo Arcila is a third-generation coffee grower from Quindio, Colombia. He is married to Luz Helena Salazar and they have two children together, Carlos and Felipe Arcila. Jairo’s first job was at Colombia’s second-largest exporter, working as their Mill Manager for over 40 years until his retirement in 2019.

Jairo has received great advice and guidance from his sons who are now experts in producing Specialty Coffee. With their help, Jairo has greatly improved the picking, sorting, and processing of his coffees. His sons have also guided Jairo in the production of exotic varieties. He now grows varieties like Pink Bourbon, Java, Papayo ,and Gesha growing across his farms. The guidance from his sons has empowered Jairo and given him the tools needed to produce fantastic coffees with amazing flavour profiles.

Besides coffee, Jairo also grows other agricultural products on his farms such as mandarin, orange, plantain, and banana. Jairo enjoys starting the day with a really good breakfast! But most importantly, he enjoys spending time with his family.

COFFEE IN COLOMBIA

Although coffee production in Colombia did not become a large commercial industry until the 19th century, it is likely that coffee was introduced to Colombia about a century earlier by Jesuit priests.

Once commercial production started, it spread quickly. The first commercial coffee plantations were established in the northeast, near the border with Venezuela. Today, coffee is widespread and grown commercially in 20 of Colombia’s 32 Departments.

Historically, Colombia’s most renowned coffee-growing region has been the Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis), also known as the ‘Coffee Triangle’. This region includes the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. With a combined total area of 13,873 km² (5356 mi²), the region covers about 1.2% of the Colombian territory and composes 15% of the total land planted under coffee in the country. The region has also been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the Eje Cafetero is still a coffee-producing powerhouse, coffee production in Colombia now extends far beyond this zone. In recent years, the departments of Huila, Tolima, Cauca and Nariño have become sought after and well-known coffee-growing regions. Today, they are the largest producers of coffee in Colombia by volume.

Today, there are an estimated 540,000 coffee producers in the country; around 95% of these are smallholder farmers with landholdings that are under 5 hectares. These farmers collectively contribute around 16% of the country’s annual agricultural GDP.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 22

AA Inoi Ndimi

COUNTRY: Kenya

FARM/COOP/STATION: Ndimi Factory

VARIETAL: SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian

PROCESSING: Washed

ALTITUDE: 1650-1800 masl

OWNER: Inoi Farmers’ Cooperative Society

REGION: Kirinyaga

FLAVOUR NOTES: Green apple, redcurrant, gooseberry, slightly herbal

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

This coffee is processed at Ndimi Factory, which is managed by the Inoi Farmers’ Cooperative Society. There are 540 active farmer members of the cooperative. The factory was named after the locality in which the washing station is located.

Perched at 1650-1800 masl, the factory sits on the foothill of Mount Kenya, just outside of the town Kerugoya. Kirinyaga County is positioned approximately 192 kilometres northeast of Nairobi, sharing borders with the Nyeri and Embu Counties. The region offers favourable conditions for coffee cultivation, featuring mineral-rich red volcanic loam soils and the elevated altitudes characteristic of the area. This western part of Kirinyaga is known to have some of the most fertile soils in the country.

Harvest

The farmers cultivate SL 28, SL 34, Batian, and Ruiru 11 varieties on clay loam soil. The coffee plants flower from February to April and are harvested from October to January. The region receives 1400 mm of annual rainfall, with an average temperature of 20.5°C.

Processing

Once the cherries have been delivered to the washing station, they are handsorted. The underripes, insect damaged, and other defective cherries are removed. The cherries are then pulped and the parchment is fermented overnight. Once the fermentation is completed, the parchment is washed and separated into P1, P2, P3, and P light. It is then dried for 10 to 20 days.

After processing, the farmers of this cooperative take the cherry pulp home and mix it with cow manure to use as fertiliser on their farms.

COFFEE IN KENYA

Despite sharing over 865 kilometers of border with Ethiopia, the birthplace of coffee, coffee had to circumnavigate the world before it set roots in Kenya. While the earliest credible reports place coffee in Ethiopia around 850 C.E., coffee was not first planted in Kenya until 1893 when French missionaries planted trees in Bura in the Taita Hills.

Under the rule of the British Empire coffee production geared for export expanded. Large, privately owned coffee growing estates were established and most harvests went to England in parchment, where it was sold to roasters prior to milling. Roasters often blended the bright flavors of Kenya with more chocolatey South American coffees.

Though large estates grew in hectarage and value, indigenous Kenyans did not benefit. In fact, European settlers took direct action to exclude indigenous people from growing coffee themselves.

In order to decrease competition, make labor accessible and inexpensive and continue the increase of demand for high-quality coffee, the Coffee Board was created to make regulations on coffee production and marketing. The Nairobi Coffee Exchange (NCE) (which continues to this day) was established in Nairobi to leave more of the value of green coffee at origin.

The Coffee Board tightly controlled licensing for coffee growing and processing. While the laws put in place did not explicitly state that indigenous people could not grow coffee, large estate owners made it functionally impossible for indigenous farmers to attain coffee growing licenses until the 1950s.

These laws protected the interests of the large landowners. Not only could more cultivation drive down the price of Kenyan coffee, but large farmers feared that if smallholder and indigenous farmers had their own coffee farms to tend, they would not work as paid laborers on settlers’ farms.

Kenya’s coffee system has been centered on a weekly auction since before independence. The Coffee Board of Kenya (now the Coffee Directorate) was established in 1933. By the following year, a government-run auction system had been established. The auction also created a pricing system that is designed to reward better quality with better prices.

Today, the auctions are widely recognized as the most-transparent mechanism for the price-discovery of fine green coffees and is considered one of the finest auction systems in the world. It even served as an inspiration for the Cup of Excellence auctions.

New legislations in 2006 and 2018 provided additional opportunities for farmers to sell their coffee. While before 2006, the auction system was mandatory, the 2006 legislation, created a “second window” made it possible for coffee growers to sell directly to international buyers.

SL-28 and SL-34 are well-known Kenyan coffee varieties. They were bred by Scott Agricultural Laboratories (SAL). SAL was founded in 1903 by the Kenyan Colonial government to function as a research institution studying agricultural products.

SL-28 and SL-34 quickly became the varieties of choice for most growers. Their deep root structures helped them acquire water in the dry environments present throughout much of Kenyan, even without irrigation. These varieties also had higher yields than the traditional French Bourbon rootstock and were considered somewhat more disease resistant.

Though both SL varieties spread across Kenya extremely quickly, the release of Ruiru-11 in 1985 by the Kenya Coffee Research Institute (CRI) brought a new kid to the block. Many farmers planted the new Ruiru-11 variety because it was far more resistant to Coffee Berry Disease (CBD), a fungal disease attacking ripening coffee cherry, and Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR), a fungal disease that targets the leaves of coffee trees. It could also be planted at a higher density than the SL varieties, allowing farmers to maximize yields on small plots of land.

One downside to Ruiru-11 was that its shallower root structure made is more susceptible to drought and required more fertilizer. Farmers found that that by grafting Ruiru-11 to SL variety trees, they could have the best of both worlds. Trees where Ruiru-11 was grafted onto an SL variety plant had deeper root structures for drought-times (thanks to the SL variety) and higher immunity to disease and larger yields (thanks to the Ruiru-11).

Other farmers are experimenting with Batian, as well, a relatively new variety introduced by Coffee Research Institute (CRI) in 2010. Batian is named after the highest peak on Mt. Kenya and is resistant to both CBD and CLR. The variety has the added benefit of early maturity and begins bearing fruit after only two years. Some challenges (such as vegetative structure) have prevented it from becoming widespread so far, but its popularity is certainly growing.

While most farms in Kenya still have the traditional SL varieties, most also have Ruiru-11 and, increasingly, Batian. Most farms are far too small to be able to handle lot separation by variety. This means that most lots coming out of Kenya—whether single estate or smallholder group—are a blend of SL, Ruiru-11 and (sometimes) Batian.

Today, more than 600,000 smallholders farming fewer than 5 acres compose 99% of the coffee farming population of Kenya. Their farms cover more than 75% of total coffee growing land and produce nearly 70% of the country’s coffee. These farmers are organized into hundreds of Farmer Cooperative Societies (FCS), all of which operate at least one factory. The remainder of annual production is grown and processed by small, medium and large land estates. Most of the larger estates have their own washing stations.

Most Kenyan coffees are fully washed and dried on raised beds. The country still upholds its reputation for high quality and attention to detail at its many washing stations. The best factories employ stringent sorting practices at cherry intake, and many of them have had the same management staff in place for years.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 21

Yetera Tulu - Lalisaa

COUNTRY: Etiopia

FARM/COOP/STATION: Yetera Tulu’s farm

VARIETAL: Local Landraces

PROCESSING: Natural

ALTITUDE: 2,242 meters above sea level

OWNER: Yetera Tulu

REGION: Sidamo

SUBREGION: Bona Zuria, Bare Kebele

FLAVOUR NOTES: Red berry jam, green grapes, purple flowers, black tea, creamy vanilla

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

Yetera Tulu inherited the farm from his family has been devoted to coffee for over 15 year. His commitment to improving his farm and delivering high-quality coffee has been continuously refined over the years. He implements best farming practices, including pruning, stumping, and planting new coffee seedlings. In the future he’s planning to expand his land and planting new coffee plants.

The combination of high altitude and nutrient-rich soil provides an ideal foundation for Samuel’s coffee to thrive. However, it is his passion and dedication that truly set his coffee apart. By cultivating shade-grown coffee and producing his own compost, he eliminates the need for chemical fertilizers, ensuring a more sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to farming.

As part of the Lalisaa Project, Yetera receives agronomy support from Sucafina Ethiopia, gaining access to training sessions that enhance his skills in cultivation, harvesting, and processing. His commitment to high-quality production and participation in the Lalisaa Project enable him to access better markets and improve his earnings. Designed to empower smallholder farmers, the Lalisaa Project shortens the supply chain, enhances quality, and increases yields.

HARVEST

Yetera, his family and additional seasonal workers carefully handpick only the ripest, red cherry. Cherry is sorted and then dry on raised beds, turning it frequently to ensure even drying. This meticulous process takes approximately 25 to 30 days, preserving the coffee’s vibrant flavors and complexity.

CULTIVATION

On his 4.5-hectare farm, Yetera embraces the principles of regenerative farming. The natural shade from intercropped plants fosters an ideal microclimate for his coffee trees. He grows a mixture of local landrace varieties—historically referred to as Ethiopian heirloom—ensuring genetic diversity and resilience. This holistic approach not only enriches the soil but also enhances biodiversity, benefiting the entire farm.

MORE ABOUT THE PROJECT: https://sucafina.com/emea/sustainability/lalisaa-project

COFFEE IN ETHIOPIA

While Ethiopia is famous as coffee’s birthplace, today it remains a specialty coffee industry darling for its incredible variety of flavors. While full traceability has been difficult in recent history, new regulations have made direct purchasing possible. We’re partnering directly with farmers to help them produce top quality specialty lots that are now completely traceable, adding value for farmers and roasters, alike.

The exceptional quality of Ethiopian coffee is due to a combination of factors. The genetic diversity of coffee varieties means that we find a diversity of flavor, even between (or within) farms with similar growing conditions and processing. In addition to varieties, processing methods also contribute to end quality. The final key ingredients for excellent coffee in Ethiopia are the producing traditions that have created the genetic diversity, processing infrastructure and great coffee we enjoy today.

Most producers in Ethiopia are smallholders, and the majority continue to cultivate coffee using traditional methods. As a result, most coffee is grown with no chemical fertilizer or pesticide use. Coffee is almost entirely cultivated, harvested and dried using manual systems.

Genetic Diversity Expands Possibilities

Exporters and importers frequently use the term “heirloom” to describe Ethiopian coffee varieties. However, this catchall-term often hides that impressive array of varieties that are unique to certain regions.

Varieties in Ethiopia can be classified into two main groups: Jimma Agricultural Research Centre (JARC) varieties or regional and local landraces.

The JARC is responsible for developing many of the varieties that flourish across Ethiopia today. JARC was established in 1967 and has been developing and sharing new coffee varieties ever since. The center also provides agricultural extension training to help farmers learn the correct cultivation methods for these newer varieties.

Landraces are plant varieties that have evolved over generations of selective breeding to be best suited to their local conditions. There are at least 130 widely cultivated regional or local landraces.

In Ethiopia, the genetic diversity of landrace coffee trees means that we find a diversity of flavor, even between (or within) farms with similar growing conditions and processing.

Processing Infrastructure Protects Quality

In addition to varieties, processing methods also contribute to end quality. Most coffee produced in Ethiopia is grown by smallholders, but they often do not have their own processing infrastructure. Instead, most smallholders deliver cherry to a wet mill. Wet mills are owned by either cooperatives or private companies.

Wet mills purchase cherry from the farmers and oversee processing. Most washing stations will specialize in both Fully washed and Natural processing methods. While the efforts of each farmer—from selecting and nurturing trees to picking on ripe cherry—are essential determinants of coffee quality, the wet mill’s practices are crucial. Wet mill staff and management are of the utmost importance, and the best washing stations employ stringent quality control measures. They only accept red, ripe cherry and have exacting drying practices. Nearly all washing stations sort drying coffee several times.

While smallholder farmer do not usually have their own pulpers, some do process coffee at their own homes using the Natural method. In these cases, coffee will be selectively picked and laid to dry on small raised beds. This coffee will usually be sold to a wet mill or collection center at the end of the season.

Preserving Coffee Producing Traditions

The final key ingredients for excellent coffee in Ethiopia are the producing traditions that have created the genetic diversity, processing infrastructure and great coffee we enjoy today.

Most producers in Ethiopia are smallholders, and the majority continue to cultivate coffee using traditional methods. As a result, most coffee is grown with no chemical fertilizer or pesticide use. Coffee is almost entirely cultivated, harvested and dried using manual systems.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 20

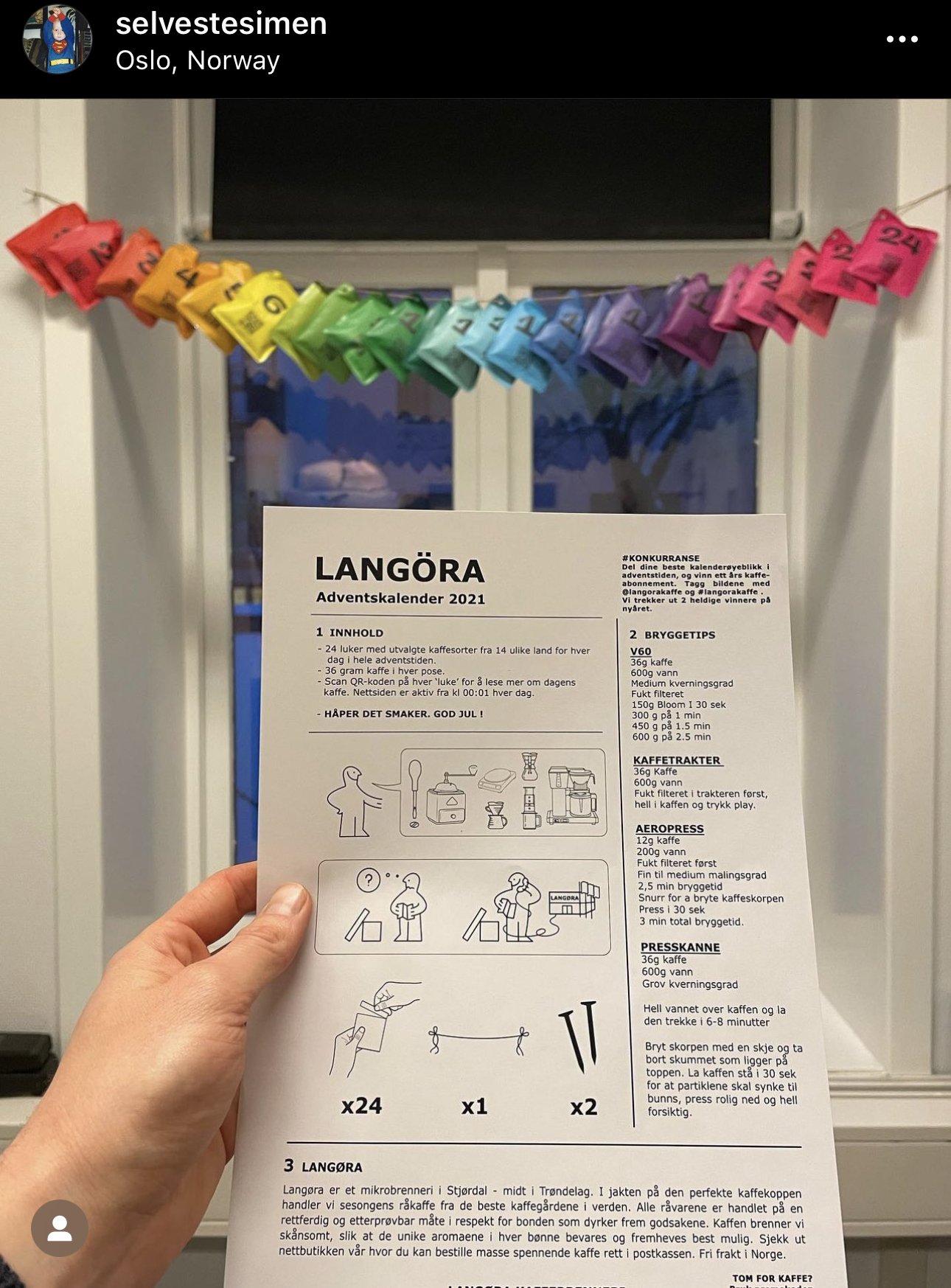

Kaffi is a small coffee roaster in Os in Østerdalen, which was founded in 2020 by Kaffi was founded in the spring of 2020 by two-time Norwegian Barista Champion Adrian Berg, and Barista Trainer and Certified Judge Silje Arnevik. Our aim was to provide education and consultancy in the field of coffee, but we needed a roastery at the core to have access to raw materials. It ended with the roasting business growing bigger and bigger and suddenly we became a full-fledged coffee roaster that in 2023 came second in the Norwegian championship of Coffee Roasting. We have also recently opened a showroom in Trondheim at Erling Skakkes Gate 39, where we open the doors almost every Friday and invite people in to taste exciting and varied types of coffee.

Sebastián Gómez

COUNTRY: Colombia

FARM/COOP/STATION: La Divisa

VARIETAL: Castillo

PROCESSING: Natural

ALTITUDE: 1200– 1800 m.a.s.l.

OWNER: Sebastián Gómez

REGION: Circacia, Quindio

FLAVOUR NOTES: plums, figs, red fruits, cacao nibs.

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

Sebastian Gomez comes from a traditional coffee family. He along with his father owns La Divisa Farm, a 13-hectare farm, located at 1.700, in Circasia, Quindío. On the farm, they have some beautiful shade trees such as Guamo, Guayacan, Gualandai, and Nogal. Sebastian is a young farmer and along with his wife both work on the coffee duties and administrative matters. His father, John, has been working in coffee for more than 30 years and has been taking care of the coffee farm since he bought the farm in 1995. Sebastian started to be more involved in coffee in 2014 when he came back To Colombia. Sebastian could witness the specialty movement in other countries, so he decided to be more involved in coffee and it was when they decided to focus on specialty coffee. They planted varieties such as Geisha and Pink Bourbon. Sebastian shared that they knew they were about to wait and just let their hard work speak out. It was three years after they could see the marvelous result. Sebastian tells us that 10 years later, quantity was the focus, but now they see a radical change since now the focus in the coffee industry is quality.Sebastian enjoys passing time with his baby and wife. He loves skating, and the best moment for him is when he goes skating while he walks around with his baby in the park.

COFFEE IN COLOMBIA

Although coffee production in Colombia did not become a large commercial industry until the 19th century, it is likely that coffee was introduced to Colombia about a century earlier by Jesuit priests.

Once commercial production started, it spread quickly. The first commercial coffee plantations were established in the northeast, near the border with Venezuela. Today, coffee is widespread and grown commercially in 20 of Colombia’s 32 Departments.

Historically, Colombia’s most renowned coffee-growing region has been the Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis), also known as the ‘Coffee Triangle’. This region includes the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. With a combined total area of 13,873 km² (5356 mi²), the region covers about 1.2% of the Colombian territory and composes 15% of the total land planted under coffee in the country. The region has also been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the Eje Cafetero is still a coffee-producing powerhouse, coffee production in Colombia now extends far beyond this zone. In recent years, the departments of Huila, Tolima, Cauca and Nariño have become sought after and well-known coffee-growing regions. Today, they are the largest producers of coffee in Colombia by volume.

Today, there are an estimated 540,000 coffee producers in the country; around 95% of these are smallholder farmers with landholdings that are under 5 hectares. These farmers collectively contribute around 16% of the country’s annual agricultural GDP.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 19

Sítio Vargem Grande

COUNTRY: Brazil

FARM/COOP/STATION: Sitio Vargem Grande

VARIETY: Yellow Catuai

PROCESSING: Natural

ALTITUDE: 1,100–1,400 masl,

OWNER: Rosimeire Aparecida Guerra

REGION: Minas Gerais

FLAVOR NOTES: Milk chocolate, yellow stonefruit, almond, red grape

Winey red fruit with plum, marzipan, and brown sugar sweetness. Coating and creamy texture with milk chocolate and black tea notes. Clean and long finish.

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

This coffee was produced by Rosimeire Aparecida Guerra on her farm, Sitio Vargem Grande in the Brazilian region of Mantiqueira, Minas Gerais.

Rosimeire and her husband Carlos were raised in families deeply immersed in coffee production, inheriting extensive knowledge and a profound passion for coffee. Carlos is the son of another coffee producer we work with, Lourdes Fatima. His brother Tiago supports him and their mother with a range of processing experiments.

Rosimeire and Carlos acquired Sitio Vargem Grande in 2009 when they got married. They selected this piece of land due to its strategic position. It sits between 1,100 and 1,400 metres above sea level, a high altitude for coffee cultivation in Brazil. The farm is 3 hectares in size, growing red and yellow Catuai which they planted in 2010. We started our collaboration with them in 2019.

Coffee holds immense significance for the entire family, serving as the cornerstone for a better future. They take pride in both their family's accomplishments and the exceptional quality of their coffee. However, their ongoing challenge lies in finding a market for their coffees while inspiring younger generations to embrace coffee production in Brazil.

HARVEST AND PROCESS

Picking

They use both mechanical and manual picking methods, depending on the harvest and ripening of the cherries. In cases where they want to increase the cup quality or create a special lot, they use selective picking.

The harvest usually takes place from June to September with the peak being in July.

Processing

Rosimeire processes her coffees as washed, as well as naturals with aerobic fermentation.

During the fermentation process they monitor the sugar content of the cherries (Brics), the temperature (which should not exceed 38 degrees), and the PH levels.

Drying

They dry coffee in a mechanical dryer, on the patio, and on raised beds. The mechanical dryer is very helpful for finishing off the drying when they need more space for new coffee coming in, or when the weather has not been adequate.

COFFEE IN BRAZIL

The story of how coffee was first introduced to Brazil is one of subterfuge, seduction and intrigue. In 1727, Francisco de Melo Palheta, a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Brazilian army, was commissioned by the Portuguese government (who ruled Brazil at the time) to steal coffee from the French, who had several nearby colonized-countries growing coffee (and had refused to share). When Brazil was asked to intervene in a border dispute in French Guiana, a country that borders the northern Brazilian state of Amapa, Palheta was sent to deal with the dispute….and steal a viable coffee seed!

After Palheta successfully arbitrated the dispute, he asked the colonial Governor of Cayenne for a sample of the governor’s coveted coffee plant. The governor refused, seeking to maintain the monopoly France had on coffee plants in the Americas. Palheta, according to legend, skirted this problem by seducing the governor’s wife. When Palheta was set to depart French Guiana for Brazil, his paramour gifted him a bouquet of flowers that had coffee beans hidden within it. The rest, as they say, is history.

In just a century, Brazil established itself as the largest producer of coffee in the world. In the 1830s, coffee became Brazil’s largest export and accounted for 30% of global production. Within a decade, Brazil had become the largest coffee producer in the world and produced 40% of total coffee grown worldwide.

Another ‘boom’ in coffee production volumes occurred from the 1880s to 1930s. At this time, Brazilian politics were controlled mainly by the agrarian oligarchs in São Paulo and Minas Gerais. This political period was called café com leite (coffee with milk) because the major money-makers in São Paulo and Minas Gerais at that time were coffee and dairy, respectively. During the café com leite period, the people who owned the large plantations in these two regions had a lot of political clout and were able to institute laws that made production and export faster, cheaper and easier.

As in so many other coffee growing countries, early coffee production in Brazil (and many other countries) was dependent on slave labor. When slavery was finally abolished in 1888, landowners finally had to pay the piper.

During the latter half of the 19th century, the lure of jobs and wealth from coffee plantations attracted millions of immigrants to coffee growing areas. During this time, São Paulo’s population grew from 30,000 people in the 1850s to 240,000 people by 1900.

Especially in São Paulo, which was the largest and wealthiest coffee-growing region in Brazil at the time, many of the jobs these immigrants found were as laborers on coffee plantations. Fueled, in part, by this labor influx, Brazil was producing 80% of the global coffee supply by the 1920s and had close to monopolistic control over the international coffee market.

Over time, as other countries began increasing coffee production, quality and export, Brazil’s market share fell. However, today, Brazil is still the largest producer of coffee and accounts for approximately 40% of global production. It’s closest competitor, Vietnam, produces a harvest that’s barely half the size of Brazil’s.

Today, the most prolific coffee growing regions of Brazil are Espirito Santo, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Bahia. Most Brazilian coffee is grown on large farms that are built and equipped for maximizing production output through mechanical harvesting and processing. The relatively flat landscape across many of Brazil’s coffee regions combined with high minimum wages has led most farms to opt for this type of mechanical harvesting over selective hand-picking.

In the past, mechanization meant that strip-picking was the norm; however, today’s mechanical harvesters are increasingly sensitive, meaning that farms can harvest only fully ripe cherries at each pass, which is good news for specialty-oriented producers.

In many cases and on less level sections of farms, a mixed form of ‘manual mechanized’ harvesting may be used, where ripe coffee is picked using a derriçadeira – a sort of mechanized rake that uses vibration to harvest ripe cherry. A tarp is spanned between coffee trees to capture the cherry as it falls.

With the aid of these newer, more selective technologies, there’s a growing number of farms who are increasingly concerned with – and able to deliver - cup quality.

Early coffee production was focused mainly in Pará, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and São Paulo. Since these regions experience significant water scarcity, most coffee in Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries was processed using the Natural method.

In more recent times, growing interest in new flavors and a more competitive market has led many producers to offer other processes including Honeys, Fully washed and newer, experimental processes like Anaerobic fermentation. Some estates have found a new niche by processing the same harvest using several different processes. The appeal of a single harvest processed in different ways is that it allows consumers to experience the effect of processing on flavor more clearly.

Due to Brazil’s significant share in global production, any changes in annual harvest size can drastically impact world coffee prices. When Brazil produces a large harvest, oversupply can drive coffee prices down. Similarly, when Brazilian harvests are unusually low—such as in years when severe frosts kill many coffee trees—global prices can increase due to a lack of supply to match global consumption.

Amongst the major coffee producers, Brazil is the only country currently vulnerable to severe frosts. Historically, severe frosts have affected harvests every 5 to 6 years.

Less severe frosts, commonly called white frosts, can impact a year’s harvest by killing the flower buds that later grow cherry. But the impacts of severe frosts resonate across several years because these frosts kill the entire tree. After a severe frost, farmers must replant most of their trees with new saplings. Young trees take 3 to 4 years to reach commercial production, so areas hit by severe frosts often have extremely small harvests for as long as 5 years following the event.

Economic events in Brazil can impact the global coffee market as well. Because of Brazil’s predominance as a coffee producing nation, fluctuations in the value of the Brazilian Real can significantly influence coffee prices.

As mentioned previously, the early coffee economy of Brazil was in some ways reliant upon exploitative working conditions. Though true for many coffee producing nations, Brazil has been visited by ghosts of its laboring past, perhaps more than others. Child and slave labor remain a concern.

Brazil has made great strides in recent years to move as far as possible from its previous labor history. Over the past 30 years, the country has implemented some of the most progressive and strict labor laws of any coffee-producing country. They have also raised a comprehensive campaign, across sectors, to eradicate modern slavery. Great efforts that have been made to make the supply chain in Brazil fairer and more equitable.

Solving this problem also relies upon every stakeholder in the coffee industry remaining vigilant. We fully support the Swiss commodity sector guidance on implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. To this end, we work closely with suppliers who share our values and who are able to prove that they follow all national labor laws.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 18

Wilton Benitez Typica Amarillo

COUNTRY: Colombia

FARM/COOP/STATION: La Macarena

VARIETAL: Typica Amarillo

PROCESSING: Anaerobic fermentation + thermoshock.

ALTITUDE:1900 meters

PRODUCER: Wildan Mustofa

REGION: Weninggalih

FLAVOUR NOTES: Peach candy, lemongrass, lime zest, earl grey, mild licorice root, jasmine

ABUT THE FARM

The farm of Wilton Benítez, located in the heart of Piendamó, Cauca, is an outstanding example of the Colombian coffee legacy. This privileged location benefits from a stable climate, where Pacific winds and low night temperatures favour the growth of high quality coffee cherries. These climatic conditions allow for a higher concentration of sugars and acidity in the cherries, resulting in cup profiles that stand out for their sweet and fruity notes. In addition, the farm's diverse terrain is ideal for the production of exceptional microlots and nanolots, each with unique characteristics that reveal the richness and complexity of southern Colombian coffee. Thus, this estate not only preserves the legacy of its founder, but also positions itself as a benchmark of coffee excellence in the region.

Innovative Process:

Anaerobic fermentation and thermal shock

When the fruits are ripe, they are harvested by hand at their optimal point of ripeness. The coffee fruit is then sorted by quality, both by size and density.

It is then subjected to two sterilisation processes:

* First, the fruit is washed with ozonated water.

* The second, the same fruit is exposed to ultraviolet rays.

The coffee cherries then undergo two stages of fermentation:

* The first is 50 to 60 hours of anaerobic fermentation at a temperature of no less than 18 °C, during which time yeast selected for the varietal or micro-batch of coffee is added. All this takes place in stainless steel fermentation tanks (bioreactors), which allow the pressure generated by fermentation to be controlled in order to bring the Brix to 6 and the pH to 3.8.

During this first fermentation phase, the mucilage is recovered and reincorporated into the fermentation environment in the next phase.

The cherries are pulped or skinned before moving on to the second phase:

*Second phase: They are returned to the bioreactors, where anaerobic fermentation in mucilage begins for 50 to 60 hours at a temperature above 21 °C.

They are then washed using a thermal shock method: first with water between 38 and 40 °C and then with cold water at approximately 12 °C. The temperature difference helps to fix the aromas produced by fermentation and to sterilise according to the temperature.

Finally, the cherries are dried in an ecological machine that allows for temperature control and recovery of the water released by the dehydration of the bean. Drying usually takes 36 hours at a variable temperature (40 °C for the first 12 hours and 35 °C for the following 24 hours).

Once the seeds from the micro-batches have a moisture content of between 11% and 10%, they are taken to the storage warehouse where they are sorted electronically and manually to meet the required physical quality standards.

Once they have the desired physical characteristics, samples are taken to the laboratory for quality verification and tasting.

The use of bioreactors, innovative drying systems, specific microorganisms developed on the farm , and constant monitoring and control of factors such as temperature, pH, Brix degrees and electrical conductivity allow for the development of more balanced coffees, with abundant tropical fruits (passion fruit, lychee, pineapple, tamarind, coconut...), providing exceptional micro-batches now available to roasters.

COFFEE IN COLOMBIA

Although coffee production in Colombia did not become a large commercial industry until the 19th century, it is likely that coffee was introduced to Colombia about a century earlier by Jesuit priests.

Once commercial production started, it spread quickly. The first commercial coffee plantations were established in the northeast, near the border with Venezuela. Today, coffee is widespread and grown commercially in 20 of Colombia’s 32 Departments.

Historically, Colombia’s most renowned coffee-growing region has been the Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis), also known as the ‘Coffee Triangle’. This region includes the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. With a combined total area of 13,873 km² (5356 mi²), the region covers about 1.2% of the Colombian territory and composes 15% of the total land planted under coffee in the country. The region has also been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the Eje Cafetero is still a coffee-producing powerhouse, coffee production in Colombia now extends far beyond this zone. In recent years, the departments of Huila, Tolima, Cauca and Nariño have become sought after and well-known coffee-growing regions. Today, they are the largest producers of coffee in Colombia by volume.

Today, there are an estimated 540,000 coffee producers in the country; around 95% of these are smallholder farmers with landholdings that are under 5 hectares. These farmers collectively contribute around 16% of the country’s annual agricultural GDP.

Colombia boasts a wide range of microclimates and geographic conditions that produce the unique flavors so loved in Colombian coffees. While there are many sub-regions and progressively smaller geographical designations — all the way down to individual farms — broadly speaking, coffees in Colombia can be separated into three major regions whose climate, soils and altitudes affect tastes.

Coffees grown in the north (Magdalena, Santander and Norte de Santander) are usually planted at lower altitudes where temperatures are higher. As such, these coffees tend to have deeper, earthier tastes with a medium acidity, more body and notes of nuts and chocolate.

Coffees coming from the central regions (Caldas, Quindío, Risaralda, North of Valle, Antioquia, Cundinamarca and North of Tolima) are celebrated for their overall balance and their fruity, herbal notes. Flavor variations highlight the specific characteristics of each micro-region.

The southern regions (Cauca, Nariño, Huila and South of Tolima) are prized for producing smooth coffees with high sweetness and citrus notes. They are also known for their medium body and more pronounced acidity.

Another distinguishing feature of Colombian coffee production is the mitaca crop – a second harvest that occurs roughly 6 months after the main crop in most regions. The mitaca crop is a result of moist ocean air rising from both the Pacific and the Caribbean, and the north-to-south orientation of the central cordilleras (mountain ranges).

Colombia’s wide range of climates also means that harvest times can vary significantly. Due to these varying harvest times — and the mitaca crop — fresh crop Colombian coffee is available nearly year-round.

Most farmers conduct primary processing (up to and including drying) on their own farms. Processing infrastructure varies widely but there are noticeable similarities between farms of similar sizes or regions. Broadly speaking, most farms have traditionally used the Fully washed method and utilized dry pulping to minimize water usage.

Drying processes in Colombia are innovative and varied. Farmers may spread their parchment across the flat roofs (elvas) of their houses to dry slowly – sometimes in the shade but more often in the sun.

In parts of Antioquia, drying ‘drawers’ are used. These are sets of moveable drying screens that can be pulled out from under the house or storage sheds when the weather is warm and pushed back under shelter when it rains.

Polytunnels and parabolic beds, also called marquesinas in Colombia, are also commonly used, particularly in high altitude and cooler temperatures zones. These structures are usually raised beds constructed similarly to mini-greenhouses with plastic sheeting stretched over an arched frame and openings at both ends to ensure airflow. These structures protect parchment from wet weather conditions while the even airflow allows for drying even in humid conditions.

As Colombian farmers are increasingly accessing specialty markets, they are experimenting with processing methods beyond the traditional Fully washed method. Producers are experimenting with all kinds of new methods and with adjustments to existing processing including changing fermentation times, adding yeasts or other products to fermenting coffee and more. They’re also producing more Naturals and Honeys of exceptional quality. And these processes are not limited to a select few. Along with Naturals and Honeys, experimentally processed coffees are now coming from a variety of regions.

Colombia’s coffee industry has been incredibly successful at building a brand that continues to help increase interest and demand for Colombian coffee. Beyond simply increasing demand, the industry’s branding made advertising history. Their iconic coffee farmer, Juan Valdez and his donkey, Conchita, were extremely recognizable.

Juan was initially created in 1958 for Colombia’s Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC) (the Federation of Colombian Coffee Growers) and his visage graces the FNC logo – along with countless of bags of Colombian coffee – to this day.

The story of Juan Valdez is just one example of the ways FNC has been a strong force in creating continuity for the reputation of Colombian coffee. Since its creation in 1927, the FNC has represented the interests of Colombia’s coffee growers. Their continued presence is almost unique in the coffee world and is, in part, one of the reasons that Colombia is such a successful coffee-producing country.

Though originally a non-profit organization, today the FNC is collectively owned and controlled by approximately 540,000 producers across Colombia. In addition to cooking up genius marketing icons, the FNC works to ensure adequate infrastructure for growers, provides technical support and funds research. Their research division, Cenicafé (founded in 1938), is renowned for its focus on developing new genetic varieties and conducting research on improved farming practices.

The FNC also seeks price stabilization and ensures minimum pricing for Colombia’s coffee farmers. Despite this, labor shortages are a growing problem in the country, as young people move out of rural coffee-growing areas into the city. This situation is the ‘new normal’ for Colombian producers and the high cost of labor is one that is a risk for many and for the industry as a whole.

In addition to its wide variety of cup profiles, the popularity of certified coffee in Colombia has grown very quickly over the past decade. The most common certifications are Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance (RFA), UTZ, and Organic. Company certifications such as Starbucks C.A.F.E. Practices are also becoming more widespread.

The increasing focus on the specialty industry is changing the way traders and farmers do business. It is becoming more common for farmers to reserve their highest quality beans in order to market them separately, at higher prices. Often, they can sell these lots with more traceability information that will reach all the way to the end customers. For farmers, having their name and life story connected to their coffee, which is then purchased and seen by the end user, brings many benefits. It means that they can nurture long-term relationships with roasters and increase the value of their product. For roasters, connecting farmers’ stories to the coffees they grew can create a stronger customer interest for specific coffees, added value and demand, and help finance successful long-term relationships with farmers.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 17

Las Nubes Lactic

COUNTRY: Costa Rica

FARM/COOP/STATION: Las Nubes Farm

VARIETAL: Caturra

PROCESSING: LACTIC NATURAL

ALTITUDE: 1800m

OWNER : Roberto Mata Naranjo

REGION: Valle de Dota

FLAVOUR NOTES: Punchy lactic acidity, cereal, overripe mango and pineapple

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

With a coffee background of almost 50 years, Roberto is a walking coffee encyclopaedia - he simply knows everything about the cultivation and preparation of coffee. Due to his experience, his closeness to nature and his love for his homeland, Roberto has been a pioneer in the sustainable cultivation of coffee in harmony with nature for decades. Three years ago, he founded a small family business together with his wife Doris and their five children. Directly behind his home, he now prepares his own coffees in his own micromill with a water-saving Ecopulper. All processes are measured, and efficiently organized, leaving nothing open to chance. Just behind their processing facility they have a small cupping space and beautifully organized sample cabinet. All of the lots are processed on raised beds, focussing purely on honey and natural lots. The metal tables and shadow nets provide the cover needed during the hottest period of the day. To create perfection in humidity, they use mechanical dryers to lower the last percentages of humidity to the correct level for export.

HARVEST AND PROCESS

All cherries are hand-picked at peak ripeness on Las Rubes Farm and meticulously sorted to remove underripe or damaged fruit. To initiate fermentation, Roberto adds a measured amount of juice from previous pre-fermented cherries to the freshly harvested whole cherries. This inoculates the batch with an active community of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts, accelerating fermentation and enhancing flavor complexity. The cherries and juice are sealed inside stainless steel tanks to create an oxygen-free environment. Over the next 72 hours, lactic acid bacteria convert natural sugars into lactic acid, lowering the pH and producing creamy, fruit-forward notes. Once the ideal pH is reached, the cherries are removed and dried in thin layers on raised African beds, turned regularly for even drying until the moisture content reaches 10–12%. The result is an intensely sweet, vibrant coffee with tropical fruit character, a silky mouthfeel, and a clean lactic finish — a signature of Roberto Mata’s lactic fermentation style.

COFFEE IN COSTA RICA

PLACE IN WORLD PRODUCTION: #14

AVERAGE ANNUAL PRODUCTION:

1,230,000 (in 60kg bags)

COMMON ARABICA VARIETIES:

Typica, Caturra, Catuai, Villa Sarchi, Bourbon, Geisha,

KEY REGIONS:

Tarrazú | Central Valley | Western Valley | Tres Rios | Brunca | Guanacaste | Orosi | Turrialba

HARVEST MONTHS:

October - March

Coffee has been a central part of the Costa Rican experience since the country’s independence from Spain in 1821. At that time, the new government led a campaign to distribute free coffee seeds to citizens in order to promote coffee production as a cash crop. Costa Rica was soon exporting green coffee beans all over Central and South America.

Just two decades later, in 1843, Costa Rica sent its first shipment of green coffee beans to England. By 1860, Costa Rica was also supplying coffee to the United States. Coffee played such a big role in Costa Rican production that coffee was Costa Rica’s only export for the years starting from independence until 1890.Costa Rican coffee farmers experience significant barriers to production. Production costs in the country tend to be very high in comparison to neighboring countries. The persistent growth of the tourist industry, combined with the influx of foreign businesses bringing more money into Costa Rica, has created inflation. While inflation and the rising quality of life have had many positive benefits for Costa Ricans, rural areas have struggled to keep up with increasing land and input prices and the associated higher labor costs. As a result, Costa Rican coffee tends to be on the expensive side.

Especially because costs are higher, Costa Rican coffee producers must find other ways to stand out from all the other producing countries in the Americas. Luckily for the specialty coffee industry, Costa Rica has had great success becoming a frontrunner in quality specialty coffees and processing methods.

In areas like Tarrazú, where conditions are ideal for coffee growing, competition is even higher. In such areas, the competitive atmosphere leads many producers to invest in private micro mills, growing exotic varieties and alternative processing.

The focus Costa Rican farmers place on increased coffee quality is beneficial to both themselves and the specialty industry as whole. An atmosphere that encourages experimentation and innovation can breed any number of new or better varieties, growing techniques, processing methods, storage protocols and more.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 16

Gitesi

COUNTRY: Rwanda

FARM/COOP/STATION: Gitesi Washing Station

VARIETAL: Red Bourbon

PROCESSING: Washed

ALTITUDE: 1750-1800 m.a.s.l.

OWNER: Alexis and Aime Gahizi

REGION: Gitesi

FLAVOUR NOTES: Sweet and clean, brown sugar, citrus, black tea

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

Gitesi is a private washing station, owned and run by father and son: Alexis and Aime Gahizi. It was built in 2005, and began processing coffee a year later. It is located in the Gitesi sector of Rwanda’s Western Province. The dynamic duo struggled to keep it operating during its launch and fought hard to turn it into a profitable business. In 2010, they finally managed to turn a profit, and have since built a sustainable company.

Alexis (Aime’s father), is originally from the Karongi District, where the washing station is located. His family has been growing coffee in this region for generations. Aime has a degree in engineering. He has created a water purification system for the washing station (wastewater management), which is being used as a model throughout the country’s coffee production industry.

With more than 1,800 local farmers delivering their cherries to Gitesi, it is important for the washing station to maintain strong relationships with the local community. Competing for cherries can be pretty tough, as farmers can deliver their lots to whichever washing station they choose. They therefore maintain a sufficient supply of cherries, and offer competitive pricing to the farmers.

Aime and his staff are very competent. They are extensively trained in managing the delivery of cherries from farmers. They have implemented strict protocols for cherry reception and sorting, as the farmers must sort out their lots themselves. If this isn’t properly conducted, the washing station has staff who can complete the task. The cherries are placed in a tank prior to pulping where floaters are removed and processed separately as lower grade coffee.

HARVEST AND PROCESS

Even though most of our selections come from cherries picked between May and July, Rwanda’s harvest can run from March until August. This isn’t always consistent, as it can shift depending on the weather and the altitude the coffee grows on.

The season’s climate in this region is generally quite cool, and can therefore control the fermentation process. A Penagos 800 Eco Pulper removes the skin of cherries, the pulp and 70% of the mucilage. The coffee is then dry fermented for 10-12 hours, graded and washed in channels. It is separated into two grades based on density, before being soaked in tanks of clean water for 16 hours.

The parchment is initially taken to pre-drying tables underneath the shade. At this stage, while the parchment is still wet, a lot of hand sorting is conducted as it is easier to detect potential defects. The parchment is then dried on African drying beds for up to 15 days. It is covered with a shade net during the hottest hours of the day, throughout the night, and anytime it rains.

GENDEER EQUALITY

Rwanda has seen significant developments in gender equity and coffee has played a role in these advancements. While women previously lost their control over agriculture during colonial rule due to gender-assumptions made by European rulers, they are starting to regain some autonomy in agriculture. New initiatives that cater to women and focus on helping them equip themselves with the tools and knowledge for farming have been changing the way women view themselves and interact with the world around them.A significant barrier to Rwanda’s expanding coffee industry is transportation. Since Rwanda is landlocked, coffee must first travel 1,500 kilometers by land to either Mombasa, in Kenya, or Dar-es-Salaam, in Tanzania. This is a lengthy and expensive process that usually costs more than it does to ship the same container of coffee from those ports to the US or Europe.

Despite the expense of transportation, Rwandan farmers are doing well. Many farmers who deliver cherry and participate in washing station programs have seen their income more than double. Additionally, the first Rwandan Cup of Excellence was held in 2008 and has since then only continued to gather traction and interest for the country’s exceptional Bourbon coffees.

COFFEE IN RWANDA

Although Rwanda’s colonial past is central to the introduction of coffee in the country, due to Rwanda’s landlocked position close to the center of Africa, few Europeans actually set foot in the country until well into the mid-1890s. Even after the 1885 “Conference of Berlin” when Germany declared control over the areas of modern Burundi and Rwanda, the first documented European traveler to ever set foot in Rwanda did not arrive until 1894.

German missionaries and settlers brought coffee to Rwanda in the early 1900s. Largescale coffee production was established during the 1930 & 1940s by the Belgian colonial government, who officially controlled the Belgian Congo from 1908 to 1960 and the twin territory of Ruanda-Urundi (that later became the countries of Rwanda and Burundi) from 1922 until independence in 1962.

The Belgian government made coffee growing mandatory during their rule. The Belgians forced native Rwandans to grow coffee in order to produce cheap, plentiful, low-quality coffee for export. Most of the profits from coffee production left Rwanda, along with the coffee itself.

When the Belgian government withdrew, many stopped tending their trees because it was no longer compulsory. For some, coffee was seen as a symbol of colonial oppression. However, many also saw the economic advantages of continuing to grow coffee, and the industry quickly became important to Rwanda’s national economy.

Coffee production continued after the Belgian colonists left. By 1970, coffee had become the single largest export in Rwanda and accounted for 70% of total export revenue. Coffee was considered so valuable that, beginning in 1973, it was illegal to tear coffee trees out of the ground.

Between 1989 and 1993, the breakdown of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) caused the global price to plummet. Considering the massive role that coffee played in Rwanda’s income, the government and economy took a hard hit from low global coffee prices. The 1994 genocide and its aftermath led to a complete collapse of coffee exports and vital USD revenue. But the incredible resilience of the Rwandan people is evident is the way that the economy and stability have recovered since then.

Modern Rwanda is considered one of the most stable countries in the region. Since 2003, its economy has grown by 7-8% per year and coffee production has played a key role in this economic growth.

This incredible recovery is due in part to the strong government support for the coffee sector as well as trade rules helping exports and international investment into the coffee sector. About ten years after the end of the civil war, the government instituted the National Coffee Strategy that helped improve and expand the coffee industry. The strategy encourages high-quality production for the specialty coffee market. Funding comes from the Rwandan government, other nations and private investors. Economic outcomes for farmers are now much better than they once were.

Previously, Rwandan coffee farmers processed their cherry at home. They would roughly de-pulp the cherry, wash it, maybe ferment it and probably dry it on the floor. This created a very low-quality commodity coffee called semi-washed. To improve the quality of coffee, the government incentivized the creation of new Central Washing Stations (CWSs) in coffee-producing areas. The first CWS was established in 2001. Today, more than 300 washing stations operate across Rwanda.

The growth of washing stations and the improvement in processing for Rwandan coffees has added at least a 40% premium to Rwandan coffee’s export value.Today, smallholders propel the industry in Rwanda forward. The country doesn’t have any large estates. Most coffee is grown by the 400,000+ smallholders, who own less than a quarter of a hectare. The majority of Rwanda’s coffee production is Arabica. Bourbon variety plants comprise 95% of all coffee trees cultivated in Rwanda.

A significant barrier to Rwanda’s expanding coffee industry is transportation. Since Rwanda is landlocked, coffee must first travel 1,500 kilometers by land to either Mombasa, in Kenya, or Dar-es-Salaam, in Tanzania. This is a lengthy and expensive process that usually costs more than it does to ship the same container of coffee from those ports to the US or Europe.

Despite the expense of transportation, Rwandan farmers are doing well. Many farmers who deliver cherry and participate in washing station programs have seen their income more than double. Additionally, the first Rwandan Cup of Excellence was held in 2008 and has since then only continued to gather traction and interest for the country’s exceptional Bourbon coffees.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 15 (Gjest)

Aya is the founder — and currently sole employee — of Hibi Kaffe.

Originally from Japan, she moved to Norway with her husband in 2013. That’s when she discovered her love for coffee and developed a deep interest in roasting.

"Hibi" means "daily" in Japanese — a reminder to better appreciate coffee in your everyday moments. Starting this journey has been an incredible experience, and I’m so excited to share my passion and craft with you.

Website: hibikaffe.no

instagram: @hibikaffe

PB Gatomboya

COUNTRY: Kenya

FARM/COOP/STATION: Gatomboya factory

VARIETAL: SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian

PROCESSING: Washed

ALTITUDE: 1770 masl

OWNER: 700 smallholder farmers

REGION: Nyeri

Bright citrus and herbal notes with raisin-like dried fruit. Long, tea-like finish and great fruit–herbal balance.

ABOUT THIS COFFEE

The Gatomboya factory is located in Konyu, Nyeri, within the Mathira division, at an elevation of 1770 metres above sea level. Established in 1987 under the Mathira FCS, it became part of Barichu FCS in 1996. The factory processes cherries from about 700 smallholders, each averaging 0.4 hectares.

The name "Gatomboya," a Kikuyu word meaning "swamp," refers to the area's swampy terrain, ideal for cultivating arrowroots. Farmers primarily grow SL 28 and SL 34 coffee varieties on rich volcanic soils, alongside other crops like tea, maize, and bananas. Shade trees such as Gravellea, Macadamia, and Eucalyptus are also planted.

HARVEST AND PROCESS

Harvest

Cherries are handpicked during the main harvest season from October to January. The water source for processing these coffees is the Kirigu River, with water being recirculated and six soak pits used for wastewater management. The cherries are sun-dried on African raised beds.

The annual average rainfall in the area is 1500 mm. The temperatures are mainly between 14 and 25 Celcius.

Processing

Farmers sort their cherries by ripeness before they go into production. They are then placed directly in the hopper that is connected to the pulping machine. The coffee flows from the hopper down to the pulper, and the pulper removes the skin and pulp (usually an Agaarde disc pulping machine). The machine is designed to conduct grading of high and low quality (1st and 2nd). Grade 1 and 2 are fermented separately, while Grade 3 is considered to be of lower quality.

The coffee is fermented for 16-24 hours under closed shade. After fermentation, the coffee is washed and graded again in channels, so that the cherries of lower quality (with lower density) will float. They are removed, leaving the denser, higher quality beans to be separated as higher-grade lots. The cherries are then soaked under clean water from the Gatomboya stream for approximately 16-18 hours.

The coffee is sun-dried for up to 21 days on African drying beds, and is covered in plastic during midday and at night.

IMPACT

The Gatomboya factory provides its members with access to credit for school fees, farm inputs, and emergencies. Its primary goal is to share information with farmers about crop management and other essential agricultural practices for coffee cultivation.

Additionally, the factory manager receives training every two years.

COFFEE IN KENYA

Despite sharing over 865 kilometers of border with Ethiopia, the birthplace of coffee, coffee had to circumnavigate the world before it set roots in Kenya. While the earliest credible reports place coffee in Ethiopia around 850 C.E., coffee was not first planted in Kenya until 1893 when French missionaries planted trees in Bura in the Taita Hills.

Under the rule of the British Empire coffee production geared for export expanded. Large, privately owned coffee growing estates were established and most harvests went to England in parchment, where it was sold to roasters prior to milling. Roasters often blended the bright flavors of Kenya with more chocolatey South American coffees.

Though large estates grew in hectarage and value, indigenous Kenyans did not benefit. In fact, European settlers took direct action to exclude indigenous people from growing coffee themselves.

In order to decrease competition, make labor accessible and inexpensive and continue the increase of demand for high-quality coffee, the Coffee Board was created to make regulations on coffee production and marketing. The Nairobi Coffee Exchange (NCE) (which continues to this day) was established in Nairobi to leave more of the value of green coffee at origin.

The Coffee Board tightly controlled licensing for coffee growing and processing. While the laws put in place did not explicitly state that indigenous people could not grow coffee, large estate owners made it functionally impossible for indigenous farmers to attain coffee growing licenses until the 1950s.

These laws protected the interests of the large landowners. Not only could more cultivation drive down the price of Kenyan coffee, but large farmers feared that if smallholder and indigenous farmers had their own coffee farms to tend, they would not work as paid laborers on settlers’ farms.

SL-28 and SL-34 are well-known Kenyan coffee varieties. They were bred by Scott Agricultural Laboratories (SAL). SAL was founded in 1903 by the Kenyan Colonial government to function as a research institution studying agricultural products.

SL-28 and SL-34 quickly became the varieties of choice for most growers. Their deep root structures helped them acquire water in the dry environments present throughout much of Kenyan, even without irrigation. These varieties also had higher yields than the traditional French Bourbon rootstock and were considered somewhat more disease resistant.

Though both SL varieties spread across Kenya extremely quickly, the release of Ruiru-11 in 1985 by the Kenya Coffee Research Institute (CRI) brought a new kid to the block. Many farmers planted the new Ruiru-11 variety because it was far more resistant to Coffee Berry Disease (CBD), a fungal disease attacking ripening coffee cherry, and Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR), a fungal disease that targets the leaves of coffee trees. It could also be planted at a higher density than the SL varieties, allowing farmers to maximize yields on small plots of land.

One downside to Ruiru-11 was that its shallower root structure made is more susceptible to drought and required more fertilizer. Farmers found that that by grafting Ruiru-11 to SL variety trees, they could have the best of both worlds. Trees where Ruiru-11 was grafted onto an SL variety plant had deeper root structures for drought-times (thanks to the SL variety) and higher immunity to disease and larger yields (thanks to the Ruiru-11).

Other farmers are experimenting with Batian, as well, a relatively new variety introduced by Coffee Research Institute (CRI) in 2010. Batian is named after the highest peak on Mt. Kenya and is resistant to both CBD and CLR. The variety has the added benefit of early maturity and begins bearing fruit after only two years. Some challenges (such as vegetative structure) have prevented it from becoming widespread so far, but its popularity is certainly growing.

While most farms in Kenya still have the traditional SL varieties, most also have Ruiru-11 and, increasingly, Batian. Most farms are far too small to be able to handle lot separation by variety. This means that most lots coming out of Kenya—whether single estate or smallholder group—are a blend of SL, Ruiru-11 and (sometimes) Batian.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 14

Las Palmas

COUNTRY: Colombia

FARM/COOP/STATION: Las Palmas

VARIETAL: Striped Bourbon

PROCESSING: Anaerobic Natural

ALTITUDE: 1,650 masl

OWNER: Efren Echeverry

SUBREGION/TOWN: Palestina

REGION: Huila

FLAVOUR NOTES: Funky pineapple, red grape, bittersweet chocolate, cranberry

ABOUT THE FARMER

Efren Echeverry is a third-generation coffee producer and current steward of Las Palmas, a family-owned farm located in Sinai, Palestina, Huila. Established 20 years ago, the farm sits at 1,650 masl and spans 7 hectares dedicated to coffee, with 5,000 trees planted.

Alongside coffee, Efren and his family grow plantain, yuca, and garden crops, taking full advantage of the area’s excellent geographic and climatic conditions.

Since taking over management four years ago, Efren has introduced meaningful changes aimed at enhancing quality, such as planting new varieties and refining post-harvest processes. For Efren and his family, Las Palmas is more than a farm; it’s a legacy and their primary source of livelihood. Today, it supports nine employees, including two permanent workers and seven seasonal pickers during harvest.

The main harvest runs from October to December, with exports taking place between May and July. Every cherry is handpicked at peak ripeness, floated to remove defects, and processed with care to ensure consistency and excellence.

HARVEST AND PROCESS

Cherries were selectively handpicked and then floated in tinas. Cherries are then anaerobically fermented for 120 hours in sealed tanks. After fermentation, cherries are dried under marquesinas (covered drying structures) for 20 to 30 days, depending on weather conditions.

Cuatro Vientos

Cuatro Vientos is a family-owned business, offering microlots and regional blends. Founded in 2018, the company was named after the first farm owned by the Gonzalez family, and therefore, holds a special meaning for them. Yonatan Gonzalez, the company’s General Manager, grew up on that farm, and is a third-generation producer with a background in logistics. His father used to commercialise coffee, as a classic, Colombian parchment buyer.

The company operates in different parts of Huila, which gives them access to coffee for 6 months per year. They have 3 purchasing points, located in each region they work in: Acevedo, Santa Maria, and Algeciras. They do not own a private drying mill, and therefore use infrastructure located in Acevedo.

The Area

Huila, along with Narino, is one of the main areas in Colombia where we can find characteristic, diverse and distinctive flavour profiles in coffee. Our partners from Cuatro Vientos work in Northern Huila (Santa Maria & Algeciras), as well as Southern Huila (Acevedo).

COFFEE IN COLOMBIA

Although coffee production in Colombia did not become a large commercial industry until the 19th century, it is likely that coffee was introduced to Colombia about a century earlier by Jesuit priests.

Once commercial production started, it spread quickly. The first commercial coffee plantations were established in the northeast, near the border with Venezuela. Today, coffee is widespread and grown commercially in 20 of Colombia’s 32 Departments.

Historically, Colombia’s most renowned coffee-growing region has been the Eje Cafetero (Coffee Axis), also known as the ‘Coffee Triangle’. This region includes the departments of Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. With a combined total area of 13,873 km² (5356 mi²), the region covers about 1.2% of the Colombian territory and composes 15% of the total land planted under coffee in the country. The region has also been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the Eje Cafetero is still a coffee-producing powerhouse, coffee production in Colombia now extends far beyond this zone. In recent years, the departments of Huila, Tolima, Cauca and Nariño have become sought after and well-known coffee-growing regions. Today, they are the largest producers of coffee in Colombia by volume.

Today, there are an estimated 540,000 coffee producers in the country; around 95% of these are smallholder farmers with landholdings that are under 5 hectares. These farmers collectively contribute around 16% of the country’s annual agricultural GDP.

Colombia boasts a wide range of microclimates and geographic conditions that produce the unique flavors so loved in Colombian coffees. While there are many sub-regions and progressively smaller geographical designations — all the way down to individual farms — broadly speaking, coffees in Colombia can be separated into three major regions whose climate, soils and altitudes affect tastes.

Coffees grown in the north (Magdalena, Santander and Norte de Santander) are usually planted at lower altitudes where temperatures are higher. As such, these coffees tend to have deeper, earthier tastes with a medium acidity, more body and notes of nuts and chocolate.

Coffees coming from the central regions (Caldas, Quindío, Risaralda, North of Valle, Antioquia, Cundinamarca and North of Tolima) are celebrated for their overall balance and their fruity, herbal notes. Flavor variations highlight the specific characteristics of each micro-region.

The southern regions (Cauca, Nariño, Huila and South of Tolima) are prized for producing smooth coffees with high sweetness and citrus notes. They are also known for their medium body and more pronounced acidity.

Another distinguishing feature of Colombian coffee production is the mitaca crop – a second harvest that occurs roughly 6 months after the main crop in most regions. The mitaca crop is a result of moist ocean air rising from both the Pacific and the Caribbean, and the north-to-south orientation of the central cordilleras (mountain ranges).

Colombia’s wide range of climates also means that harvest times can vary significantly. Due to these varying harvest times — and the mitaca crop — fresh crop Colombian coffee is available nearly year-round.

Colombia’s coffee industry has been incredibly successful at building a brand that continues to help increase interest and demand for Colombian coffee. Beyond simply increasing demand, the industry’s branding made advertising history. Their iconic coffee farmer, Juan Valdez and his donkey, Conchita, were extremely recognizable.

Juan was initially created in 1958 for Colombia’s Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC) (the Federation of Colombian Coffee Growers) and his visage graces the FNC logo – along with countless of bags of Colombian coffee – to this day.

The story of Juan Valdez is just one example of the ways FNC has been a strong force in creating continuity for the reputation of Colombian coffee. Since its creation in 1927, the FNC has represented the interests of Colombia’s coffee growers. Their continued presence is almost unique in the coffee world and is, in part, one of the reasons that Colombia is such a successful coffee-producing country.

Though originally a non-profit organization, today the FNC is collectively owned and controlled by approximately 540,000 producers across Colombia. In addition to cooking up genius marketing icons, the FNC works to ensure adequate infrastructure for growers, provides technical support and funds research. Their research division, Cenicafé (founded in 1938), is renowned for its focus on developing new genetic varieties and conducting research on improved farming practices.

The FNC also seeks price stabilization and ensures minimum pricing for Colombia’s coffee farmers. Despite this, labor shortages are a growing problem in the country, as young people move out of rural coffee-growing areas into the city. This situation is the ‘new normal’ for Colombian producers and the high cost of labor is one that is a risk for many and for the industry as a whole.

Check out more coffees in our store:

Luke 13 (Gjest)

SCANDINAVIAN ALPS

This project started because we have always been passionate about skiing and coffee. The main source of our inspiration came from our late grandfather who helped introduce us to skiing in the Alps and amazing coffee in his home city of Vienna, Austria. Today we have combined these two passions to make great artisanal coffee in one of the most beautiful places in the world, Hemsedal, Norway, "The Scandinavian Alps".

Adrian Seligman